Building great software is fraught with peril, and there are countless decisions that can alter the path of your final product. Hundreds, even thousands, of decisions will need to be made, from the simple such as naming your product, to the more complex—like who to hire—and so on. But the most paramount is precisely what—and when—to ship.

Releasing a product which does not have engaging and interesting features yields software users will not even give a chance. On the other hand, putting every bell and whistle you can dream up into the product will likely prevent it from ever shipping (with a nifty side effect of draining your bank account in the process). This principle keeps many entrepreneurs awake at night and can strike fear in the most experienced businessman. Due to the volume with which mobile products are released, a new app often has one fleeting chance of success. Any mistake may doom a new app to the dark dusty corners of the App Store.

Before you can even begin planning a project you first need to understand what a minimal viable product (MVP) is, and what it is not. The term has been tossed around Silicon Valley as carelessly as ‘Web 2.0’ was a dozen years ago. Every investor wants a minimal viable product so they can test the waters of the market without spending all their money. It has also become a funder’s synonym for “don’t waste money”.

To understand the minimal viable product, you must first understand the core purpose of the product.

For example, consider a product which allows two people to communicate using their voice over long distances. (A modern cell phone can be considered a completed project state for this idea.) What is the minimal viable product for this type of device? Is it a cell phone without any of the bells and whistles? Perhaps a Nokia 3310? Building a Nokia 3310 for a minimal viable product is a huge mistake. The cost of such an endeavor would be gigantic without the desired low cost market testing. This hypothetical communication project will require most of the effort of a modern cellphone before it can prove the initial market case, do people even want to communicate via voice over distance? Granted, the Nokia 3310 isn’t nearly as advanced as a modern iPhone, but as we will see it is a far cry away from minimal by several measures.

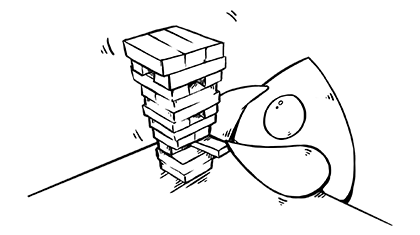

This is the fork in the road where most business owners make their first mistake, sadly it’s a blunder that is often unrecoverable. It is hard to detach yourself from the final product vision, but you must be detached to create a true minimal viable product if you aren’t working with a virtually unlimited budget. When building a cell phone, a minimal viable product is not a stripped down phone with only the 4 key and a microphone, but no speaker, this would not solve the initial problem of long distance voice communication. This stripped down phone is a non-viable product and the reason most MVPs will fail. What commonly happens is the entrepreneur takes their final version and strips out features until they have the empty body of a 1973 Chevy Impala collecting rust on their lawn, all the while wondering why no one is interested in investing, or even driving, their new car prototype.

Contrary to popular belief — most minimal viable products won’t even resemble the final vision, and in all likelihood can’t even be easily converted into the final vision. Take for example the voice communication device discussed above. The MVP for such a device would likely be 2 cans between a string. Ridiculous? You bet. However its much more practical than a cell phone with no speaker and only a 4 key. The cans with a string actually solves the problem: it lets two people communicate over distance. This MVP will also test the market to see if people have any interest in communicating with another party over distance. Yes, it is limited, but that’s the entire point of an MVP. There is no easy way to add a couple of features and turn the can solution into a smartphone, but that’s exactly the point.

Once the can and string method is tested, the next phase of development can be started. Assuming the market warrants the work, a landline rotary phone is a reasonable next step. The problem is you can’t just convert two cans to a rotary phone — they contain completely different technology. Even more so if you were to try and jump to an iPhone as the next step. This holds true in software as well. The initial MVP likely will not easily convert to the more advanced product.

Business owners tend to make the mistake of offering a stripped down version of their final product and calling that an MVP.

A minimal viable product is only minimal in the sense that it completes the purpose of the project without adding additional features. It is not a version of the end product with a bunch of features disabled. Going from an MVP to final product likely won’t just be a minor upgrade — it will likely be a complete rewrite and redesign.

Deciding on what should be in the minimal viable product is a hard decision and one that can change the future of a company. Making a mistake with too little, or too much, can be disastrous. Whether your project is a new consumer product, invention, or mobile app — with every step of the products life the core problem needs to be solved.

There should be a key problem that can be described in a couple of sentences about the problem your product is solving. Looking at some popular software products, we can abstract their original key problem.

- Square — There is no easy way for users to accept credit card payments on a smartphone.

- Uber — There is no centralized service for easily calling for a private car.

- Facebook — There is no system for college students to easily communicate or find each other.

- Slack — Email communication is too slow and inefficient for the modern office.

- Dropbox — Sharing large files is complicated and slow.

Each of these successful tech companies can be distilled into a very simple problem that they set out to solve. While their products may have evolved to solve even bigger problems, they started out trying to solve a very basic core problem that was a pain point for users. A key problem should be clear, short, and relatable — it should also be the beginning of your elevator pitch.

When you start including how the product works you shift from the problem to the features, focus on the problem to start, not the solution. Once you understand the problem than you can think of the absolute simplest of solving the problem. This might be completely different than the product you have been dreaming about, it might be a better product, or more likely it will be the MVP. It will allow you to test the waters without going broke and more importantly it will save you months (or years) of time building something which will never see the light of day.