Introduction

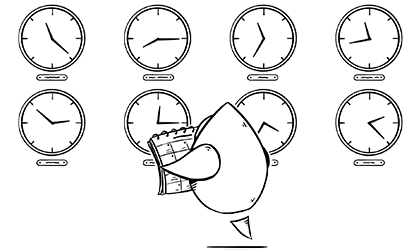

“What time is it?” has been an important question to humans for quite some time. For most of history, we only cared what time it was here: When will it get dark? When will it get light? When will this woolly mammoth fall into my cunning spike trap? Then, things got more complicated. I’ve sailed halfway around the world, and the people here think it’s the year 4567, not 1800, what’s up with that? I have a teleconference next week with my client, on US Central time, and the clocks here in England change for daylight savings this weekend - am I going to miss it?

It gets complicated. It’s a giant, interconnected world, and time is an important component of the data that flows around it. Dates have an added level of difficulty because bugs in date handling code can appear nondeterministic - they tend to occur only at certain times of the year, or in certain places. How can you deal with time data in your apps without spending all of your time on it? In this post I’m going to give you some practical tips and standards for dealing with dates in Apple’s Foundation framework.

The Date type

The #1 tip for dealing with dates successfully is to always use Foundation’s Date type. Standard library programmers have spent far more time, with far more real-world use cases, dealing with dates than you or I ever will. Your idea is probably not better.

Date is a very simple type. It only holds one piece of data - a number of seconds. This is the number of seconds since (or before, if it’s negative) a reference date, which is a known point in time. A Date does not contain any information about months, days, years, hours, minutes, or time zones. This is a crucial part of information to absorb. The reference date is 00:00:00 on January 1 2001, UTC, but that doesn’t mean that Date is “in” UTC, or the Gregorian calendar. The reference date was picked presumably for reasons of cultural background and expediency (the UNIX reference date is 1 January 1970, and we’re approaching the point where a 32-bit integer can’t hold how many seconds ago that was). Foundation’s date programmers, with their fancy 64-bit integers, have kicked the can down the road for a couple of million years at least.

The common misunderstanding that Date encapsulates calendar and time zone information probably stems from the fact that when a Date is shown in the debugger, it doesn’t give you a meaninglessly huge number of seconds, but a formatted date. This is the source of literally hundreds of Stack Overflow questions, as programmers quite naturally get confused by creating a date in a certain fashion, examining it in the debugger, and seeing a displayed version which is a few hours off from the one they expected to see. When a Date prints its description, it does some work in the background, then shows you the represented time in UTC. Here in England we only get confused by that for half the year, the rest of the world gets it rather worse.

So, how does a Date get turned into a recognisable date string? A Date is largely meaningless unless it is associated with a Calendar. A calendar represents an agreed system of naming points in time. The most widely used calendar around the world is Gregorian, but there are several others, for example the Islamic and Hebrew calendars. The calendar can interpret a Date and make it into components, such as a year, month or day.

Just a calendar isn’t quite enough to know the answer to “what time is it?”, though. The calendar can tell you what system of counting time and date is in use, but it’s also important to know which TimeZone you are in. This type represents all of the information about a time zone, including the offset from UTC / GMT, and daylight savings transition dates.

The calendar gives you components - but that’s not what you see when you view a date in the debugger or on the screen. A printed date is created by a DateFormatter, which also has the final part of the puzzle - the Locale. A locale tells the system how people from a certain place and / or language prefer to see dates - the classic example being the US locale, where dates are written incorrectly (1/31/2018) and more sensible parts (i.e. the rest) of the world, where we put the day at the start (31/1/2018).

All of this complexity is hidden from you when you get the debug description of a Date - internally it uses a date formatter, with the Gregorian calendar, a fixed format including all of the pertinent information in a consistent order, and the UTC time zone. Sometimes, the magic gets in the way of knowing what’s happening.

Armed with the knowledge of the types that Foundation uses to process and understand dates, you can now think more clearly about how to deal with them in your code.

Dates coming in

Dates will enter your app in three main ways. In all cases your goal is to get to a Date as soon as possible:

- You record the time that an event happens, by creating a

Date. That’s easy; you’re done. - The user enters a date. If you use a system date picker control, you’re almost done. If your picker is in time only or date only mode, then bear in mind it will fill in the missing parts using the time that the picker was created. For example, if the user opens a screen with a date-only picker on it at 12:30:34, then sets the month and day, the final date will be at 12:30:34 on the selected day. If that’s not what you want then you’ll need to extract date components (see below) and build your own date. If you’re using your own control, you’ll need to get date components out of it and build your date yourself.

- A date comes in as part of an API response. This is where the “fun” can happen. Imagine how many programmer hours would have been saved if the JSON specification included a standard for dates!

Strategies for dealing with incoming strings-as-dates

- ISO8601 “standard” format sounds nice but it’s not a silver bullet - the Foundation-provided

ISO8601DateFormatterhas a 14-member option set for dealing with the different formats that apparently still count as conforming to this. If this formatter works for you, use it. - Try to make sure that the date format used in the API contains as much information as possible - year, month, day, hour (in 24h format), minute, second and a time zone offset from UTC. The system that’s making these API responses should be holding dates as something analogous to

Date, so the information should all be there. If it isn’t, you may need to run away. Raw timestamps (seconds since the start of the UNIX epoch) can be useful since they unambiguously incorporate all of this information, but they are much harder for humans to read during development and debugging. - Try to make sure that every single date sent to you from the API vendor is in the same format. Battle-hardened programmers will be rolling their eyes at the naiveté of this ambition.

- By default, date formatters take a lot of context from the device they’re running on. This is to aid production of strings from dates in a manner that the user will find familiar and understandable, or to interpret user-entered strings as dates in an expected way. But when you’re making dates from strings that have arrived in a fixed format, you have to be absolutely clear with the date formatter. To do this, you have to set a special locale -

en_US_POSIX, which ensures that user preferences such as 12 hour date formatting are ignored. That special locale, coupled with a precise date format which specifies the time zone, should make sure your incoming dates are interpreted consistently, for users worldwide. Apple’s technical note and the Unicode date format pattern guide are good references, and you can interactively play with formats and find references with the excellent NSDateFormatter.com. A common mistake is to use Y instead of y for year - upper case gives you the year in “week of year” based calendars, which is mostly right, except when it’s wrong.

Date calculations

What time is it one second from now? One day from now? One month from now? The first question is almost always fairly straightforward, the last two less so. The two things that can bite you are calculations that span daylight savings transitions, and the plain oddness of most calendars - months are different lengths, we have leap years, and so on, which are a rich seam of rarely-occurring bugs.

Date has a method for obtaining a new date X seconds away from a given date. It’s tempting to use this when doing date calculations, but it’s not always appropriate. In reality there are two different things you may be concerned with when doing date calculations - the absolute difference between two times (so this has to happen in one hour, like a kitchen timer), or something that has to happen at a specific time in the future (this has to happen at 5pm next Tuesday). For the first kind of calculation, you can absolutely just add a time interval to a date. For the second kind, you should drop out to date components. Think of date components as the parts of the date that you’d expect to see if you looked at your watch at that time. A calendar can translate between date components and dates, and you can use date components for calculations. The calendar takes care of any daylight saving transitions and leap years and can be given rules for rolling over units, when you’re adding a month to 31 January, for example.

Always use date components and calendars when performing date calculations - don’t do things like get a string out using a date formatter, manipulate the string, then pass it back in. It’s more code, and you’ll get it wrong. For simple calculations, it’s a one-liner to use components:

let inAMonth = calendar.date(byAdding: .month, value: 1, to: date)

Dates going out

There are two destinations for your outgoing dates - back onto the web, in which case you can ideally use the same formatter you used for incoming dates, or onto the screen, in which case you should respect your user’s locale and preferences - stick to the built-in time and date styles (short, medium, etc), rather than hard-coding a format that may not make sense to users worldwide.

So, what time is it?

🍻 o’clock! Thanks for reading!