Two months ago, I made the decision to throw out months of work on one of our game development projects. For Republic Sniper, we made a fresh start, turning our back on months of work and switching to a new game engine: Unreal Engine 4. It wasn’t an easy decision to make. None of the code or shaders we wrote for Unity could be brought over to UE4, and there’s a fair bit of work involved in bringing over the 3D models and image assets we’ve created.

We’ve now been using UE4 in anger for a couple of months, and one thing has become very clear: We made the right decision. The pace of development has increased substantially since making the switch and the latest builds look much better. Much more importantly, the Republic Sniper team is happy with their tools and once again feel good about what we’re creating.

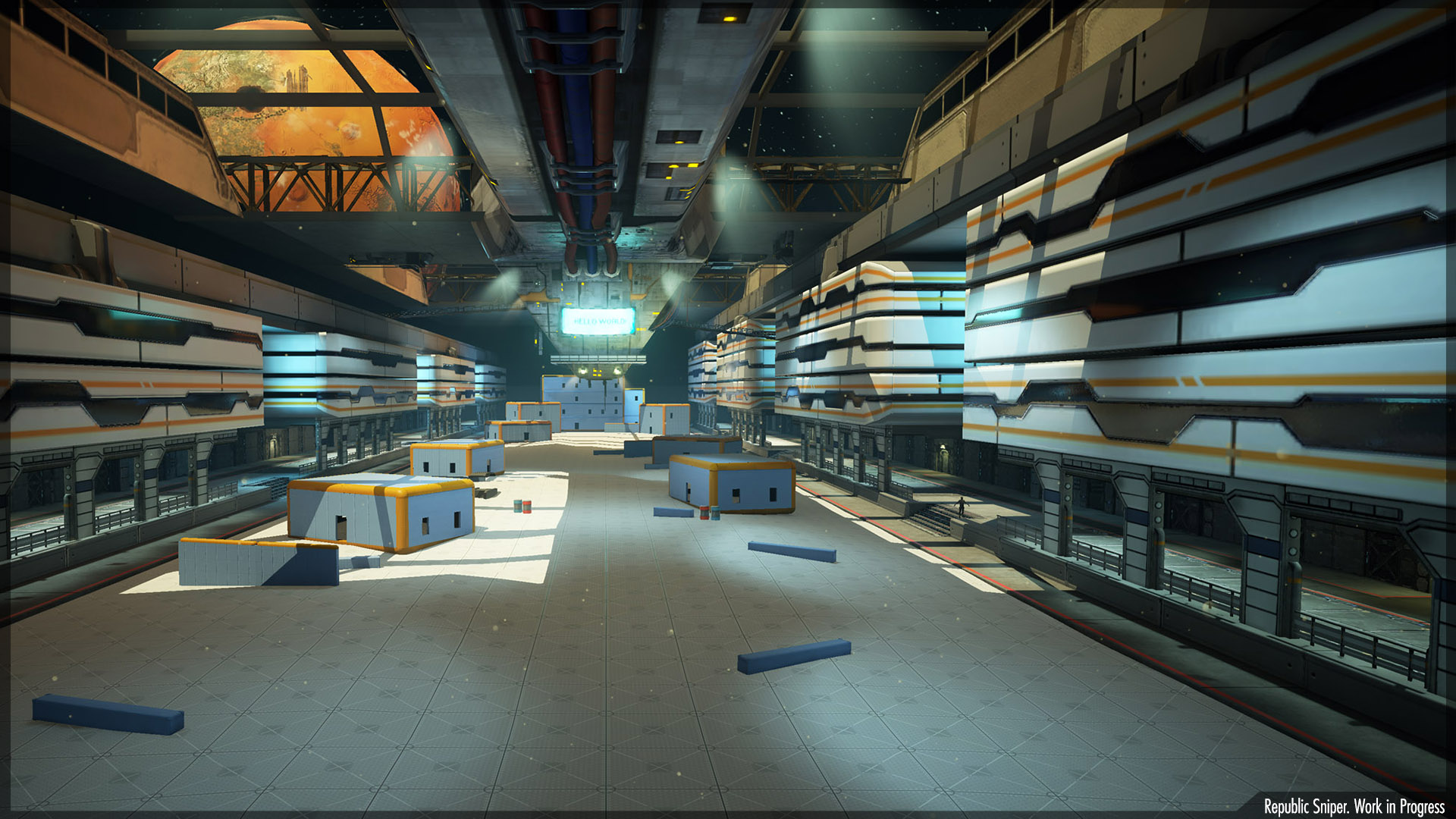

A WIP in-engine screenshot of the last Unity version of Republic Sniper before we made the switch

Our Blue Period

By June of this year, the team had become frustrated with our Unity workflow and wanted to explore other options. Once we started, it didn’t take long to see that the best alternative — and possibly the only viable alternative for us — was the Unreal Engine. After a few weeks of experimenting, reading documentation, and test driving the latest version (UE4), we were convinced that we needed to make the switch.

That doesn’t mean the decision was made without trepidation. We had a lot invested in the Unity version of Republic Sniper and walking away from it was more than a little scary.

A WIP in-engine shot of the current Republic Sniper training range in UE4

Fear of the Sunk Cost

In a past life, I spent about a decade as a consultant working in Enterprise computing. I traveled constantly and did programming, database, and integration work for very large corporate and governmental entities.

In that role, I repeatedly saw bad decisions — often to the tune of tens of millions of dollars — being made simply because a large investment of time and money had already been made pursuing that bad decision. On many projects, I watched people stick by decisions long after everyone on the project knew it was a bad one.

The funny thing about the sunk cost fallacy is that when you’re an outsider — with no skin in the game — it’s really obvious when it’s time to cut losses and try something new. When it’s not your money, reputation, or job on the line, the tough choices are a hell of a lot easier.

I didn’t have the luxury of being an outsider with Republic Sniper. When I started to realize that, perhaps, Unity wasn’t the right choice for us, I didn’t really want to accept it. It took a a couple of months and required exuberant lobbying by certain members of the team for me to authorize the switch.

WIP shot of the shooting stalls on the training level

The Unity Fit Problem

Unity is a very capable tool, and a lot of really good games have been made with it. We absolutely could have finished Republic Sniper using Unity. We could have pushed through our frustrations and delivered a respectable game.

Only… nobody on the team would’ve been happy making a respectable game.

The First Sign of Trouble

I first started questioning our use of Unity early this year. As we started to explore just what we could accomplish in a mobile game, we started having significant problems. The Unity Editor is still — in 2014 — a 32-bit application. While the theoretical memory limit of a 32-bit Mac App is 4 Gigs, on a machine with dual GPUs, you actually only get an application heap of about 2.7 Gb of RAM in practice. When a 32-bit app hits that memory limit, you start getting erratic behavior and crashes that give you very little information about what happened. While 2.7Gb may sound like quite a lot of memory, we found ourselves hitting the limit regularly.

I wasted weeks of time figuring out the problem. In the process, I lost a substantial amount of work to memory crashes. I filed dozens of bug reports, but none of them yielded a satisfactory response from Unity’s tech support. Nearly every ticket was closed with no acknowledgement that maybe a 32-bit application in 2014 — 8 years after Apple stopped shipping 32-bit-only computers — might be anything less than perfectly reasonable. No matter how many times I asked, I got no hint of when a 64-bit editor might be coming out. All of my interactions with Unity tech support left me frustrated and feeling, frankly, like they didn’t care all that much.

The Real Problem

There were other technical issues along the way, though none as severe as the constant memory-related crashes. Yet, the technical issues were not what made us start looking for alternatives. Nor was it Unity’s weak customer service responses to our legitimate frustrations. Our team just wasn’t finding it easy to collaborate. We weren’t gelling as a cohesive team and we often felt like the tools were working against us.

An in-engine shot from the catwalks

Every time we pulled code updates from source control or switched target platforms, Unity would take at least forty-five minutes to open our project, and considerably longer on less powerful hardware. The solution to this problem — a problem that screams design flaw — was for us to use the Unity Cache Server at an additional $500 per seat.

Being able to use version control effectively or to switch platform targets on a large project without having to wait for an hour is an add-on feature, not included with the Professional license?

Yes.

But really, that was just one symptom of a larger problem. The real issue was that Unity seems to have been built for very small development teams. While Republic Sniper isn’t a huge project, we have seven regular project members and a number of other contributors.

There are upsides to Unity’s approach: It allows tiny teams to create things that used to be impossible for small teams to build. Unity has enabled some truly phenomenal indie games, many of which were created by a single developer.

Unity is also a very developer-centric toolset. Our game artists honestly hated working in the Unity Editor and felt like second-class participants in the game development process. They were constantly waiting on a developer to write a shader or component for them and the tools felt alien. We had constant bottlenecks, and were never happy with the look & feel we could achieve, despite a lot of time and effort invested into the art design and production.

Enter Unreal

I’ve known about the Unreal Engine for a very long time. Indeed, many of the games that inspired me to create games display the Unreal Engine logo when launched. Despite that, we didn’t even consider using Unreal when we started Republic Sniper. The UDK (the previous version of the Unreal Engine dev tools) took 25% of your gross income after the first $50,000. When you added that 25% to the 30% taken by the app store, it meant we’d be losing more than half of our gross income. The other big obstacle was that the UDK tools were Windows only. MartianCraft is a shop of (mostly) dyed-in-the-wool Mac folk who’d rather not spend their days using Windows.

When UE4 came out with a license cost of $19.95 per month per seat plus 5% of gross, a Mac version of the tools, and full access to the underlying source code, we decided to take a long, hard look at it.

UE4’s physically-based rendering is gorgeous. It runs well on iOS devices and looks absolutely fantastic on the latest generation of hardware. The editor and tools are very artist-friendly. More importantly, UE4 has two options for programming: C++ and a visual programming language called Blueprint.

An in-engine shot of one of the rifles available in the game: the LT-4 “Hellfire” Tactical Sniper Rifle

Blueprint

I’d never been a fan of visual programming languages before, so I didn’t pay much attention to Blueprint at first. But when one of our code-phobic artists sent me a small game level, complete with programmed interactions, that he had put together after a couple of days of tinkering, I was curious.

The way Epic has designed Blueprint and C++ in UE4 to work together is pretty amazing. You can write a C++ class and then subclass it in Blueprint. You can expose C++ methods to use as Blueprint nodes. Almost everything you can do in C++, you can do in Blueprint. Although there is a small performance hit with Blueprint, it’s rarely enough of a hit to be an issue. Both languages are first-class citizens in the engine, and there are very few tasks that require C++. For some tasks (especially tasks with complex algorithms), C++ will likely be the better choice for experienced programmers, but almost nothing has to be done in C++.

And that is incredibly empowering.

For visual thinkers, Blueprint just makes a lot more sense than lines of text-based code. It’s also a lot less intimidating. In fact, Blueprint has enabled our game artists to accomplish many tasks by themselves that would’ve required a developer when we were using Unity. This has made us much more efficient and faster as a team. While people still specialize, most tasks can be handled by anyone on the team. The logic for opening a door, for example, might be written by a programmer, but it might also be put in place by a level designer or modeller. It can even be started by a level designer then polished, and tweaked later by a developer who can also make it more efficient.

Goodbye Shading Language

UE4’s physically based material system produces great results, and the way you build shaders for it is similar to Blueprint. UE4 uses a visual node-based material system much like those familiar to our 3D artists from other applications. The artists never have to see cryptic GLSL or HLSL code. There’s no ShaderLab or CG or a need to wait for a shader programmer’s help to get the look they want. The whole material system is visual, it all makes sense to artists, and the results are jaw-droppingly fantastic in the hands of a good artist.

Miscellany

Although we’ve barely scratched the surface of what UE4 can do in the few months we’ve been using it on Republic Sniper, we’re constantly finding little unexpected treats; things that are easier than we were expecting. Building an iOS app, for example, doesn’t require exporting our project to Xcode and then compiling and code signing. We can build within the Unreal Editor and deploy test builds directly to a device for testing. Heck, even those black sheep on our team who work on Windows can build for iOS with Unreal.

Unreal also has much better built-in tools for most common game development tasks, including great tools for creating physics assets (ragdolls), designing character AI, and doing dynamic level loading and unloading. Lightmap baking is considerably faster and the interface is far more intuitive than Unity’s.

The Downsides

It’s not all grins and giggles, though. UE4 is a relatively new toolset with a lot of brand new, completely rewritten functionality, and there have been bumps along the way. There are a few parts of UE4 that simply feel unfinished and we’re still climbing a learning curve as we adjust to a UE4-based workflow. We’ve opened many bug reports over the last couple of months. Fortunately, Epic has been responsive to our bug reports and seems eager to make UE4 meet our needs. The UE4 development community has been helpful and supportive as well, and we’ve seen regular feature releases and bug fix releases since we started using it.

Since UE4 is the first release of the Unreal Engine to really go after small and medium size game shops, there’s currently no comparison between the new UE4 Marketplace and Unity’s Asset Store. The Unity Asset Store is a thriving marketplace with a lot of great tools and content. It will be quite some time before the UE4 Marketplace has a comparable amount of content. This hasn’t been a problem for us because we have our own content creation team for Republic Sniper and most of the Asset Store items we bought for Unity were to accomplish tasks that UE4 handles natively.

The single biggest issue for us with UE4 has been the performance of the Mac editor, which lags considerably behind the Windows version when running on the same hardware. This is a little frustrating, since the introduction of the Mac editor was one of the draws that lead us towards UE4 . Mac performance is bad enough that it’s painful to run the UE4 Editor on a laptop or an older desktop. I find the performance quite acceptable on my Late 2013 Mac Pro, but when I work on my 2012 Retina MacBook Pro, or at home on my Mid-2010 Mac Pro, I resort to bootcamp and the Windows version of the Unreal Editor to get work done.

The Final Word on UE4

There’s no such thing as a flawless or perfect set of development tools — UE4 is no exception. However, despite a few rough edges, I’m incredibly happy with the switch. UE4 is a professional toolkit in all respects, honed over more than sixteen years and dozens of AAA game titles. Despite that, it’s also an extraordinarily approachable toolset. UE4 allows us to create a game that lives up to our expectations and we’re really excited once again to be making this game.

Don’t read this as a condemnation of Unity. We’re still using Unity for another game project and have no intention of switching it to UE4. Unity is a great fit for that project, just like UE4 is a great fit for Republic Sniper. A year ago, Unity was the undisputed leader among an anemic set of game engines for indies and small game studios. Now, we have two strong options with their own strengths and weakness. For some projects, either tool will work well. For other projects, one may be a substantially better fit.

As a company that does both in-house and contract game development, having more options is a great thing. We believe strongly in using the best tool for any given job. The more good tools we have available, the more likely we are to find the right tool.

Epic’s decision to go after Unity’s market also means increased competition. That competition will push both companies to make better tools. That’s a good thing for game developers and ultimately for people who play games.

Republic Sniper Progress Update

If you’ve read this far, you might be interested in knowing what’s been going on with Republic Sniper since my last Dev Diary posting.

Well, frankly… a lot.

In addition to a new engine and more polished visuals, we’ve really started to dive into gameplay. We brought in an experienced game developer, Thomas Ingham, to take over as Lead Programmer on Republic Sniper when we made the switch to UE4.

This allows me to focus more on universe development, dialogue, and story, while Thomas leads the day-to-day development effort. As a result, my other responsibilities here at MartianCraft no longer bottleneck the project or disrupt the project schedule.

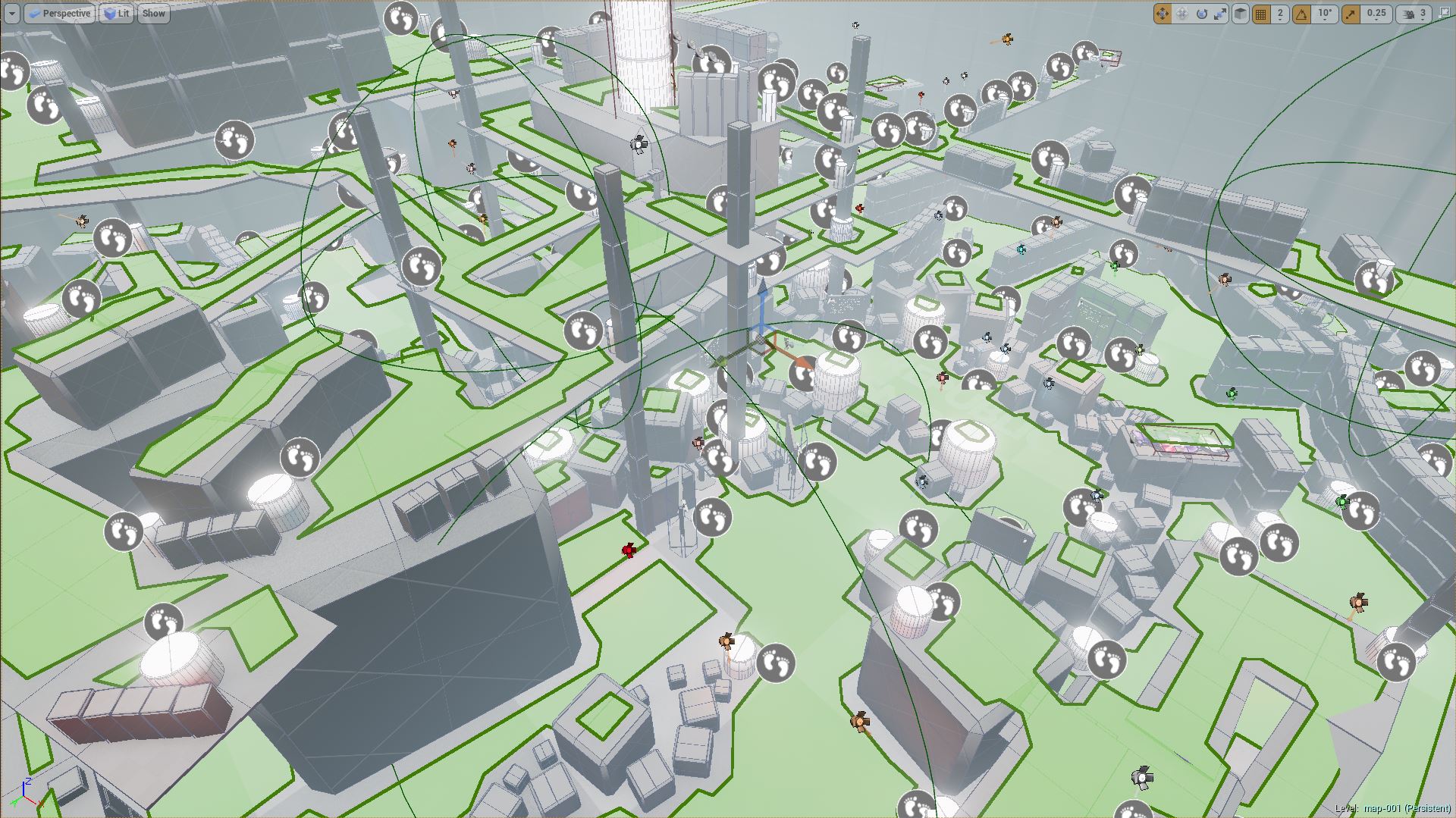

Thomas has done some great work. He has come up with a novel movement mechanism that works really well on touchscreen devices. This new mechanic makes for a more interesting game and also brings back some of the stealth elements from the earliest Turncoat prototypes.

Schematic of level we’re using to test our new movement mechanics.

Shortly after the switch to UE4, the Republic Sniper team came to me with a great story hook for the game; something to pull the player right in from the start. I loved the idea, but it wasn’t entirely compatible with the original concept or backstory. Now we’re working on making that hook fit into the Universe consistently.

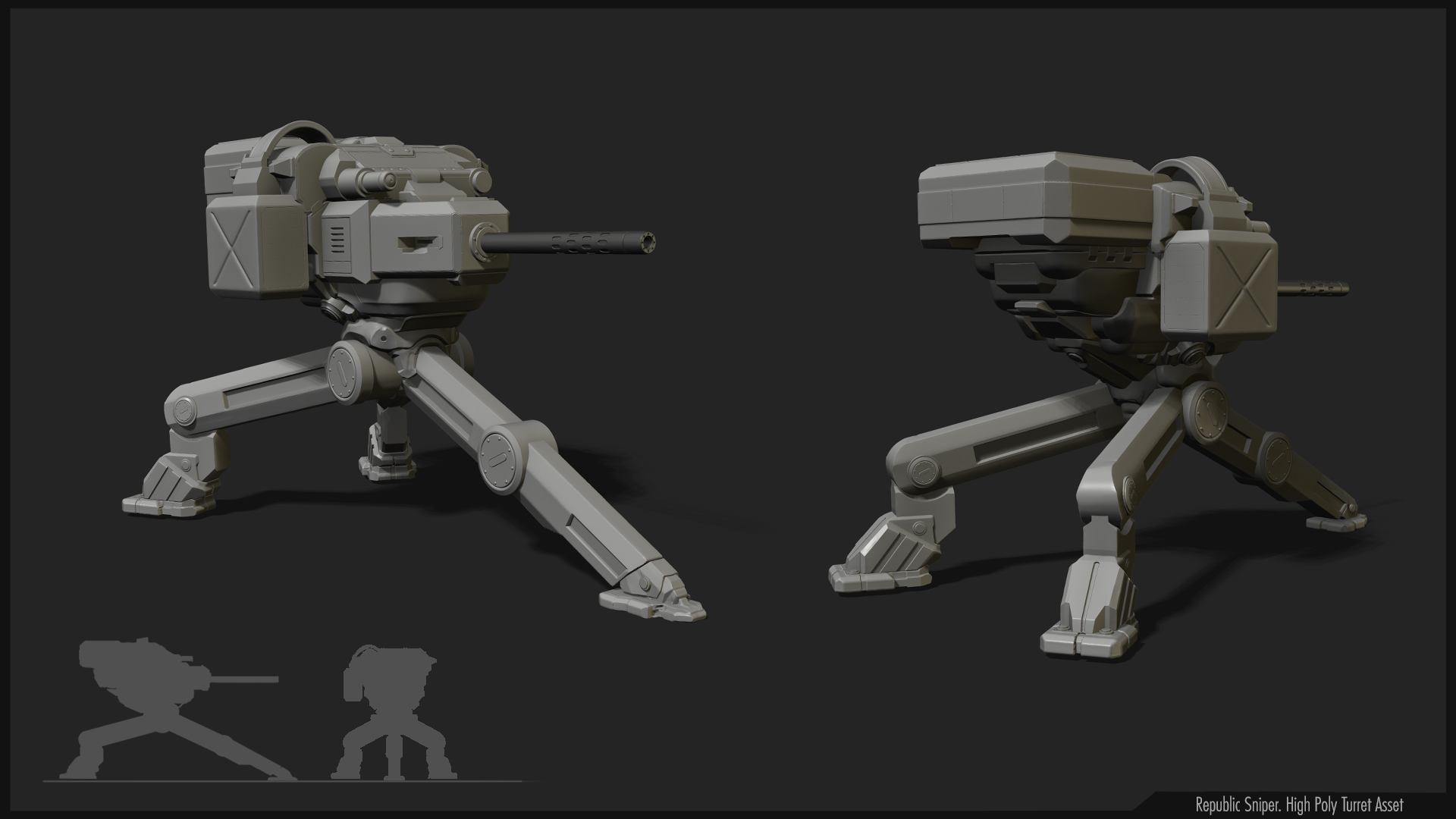

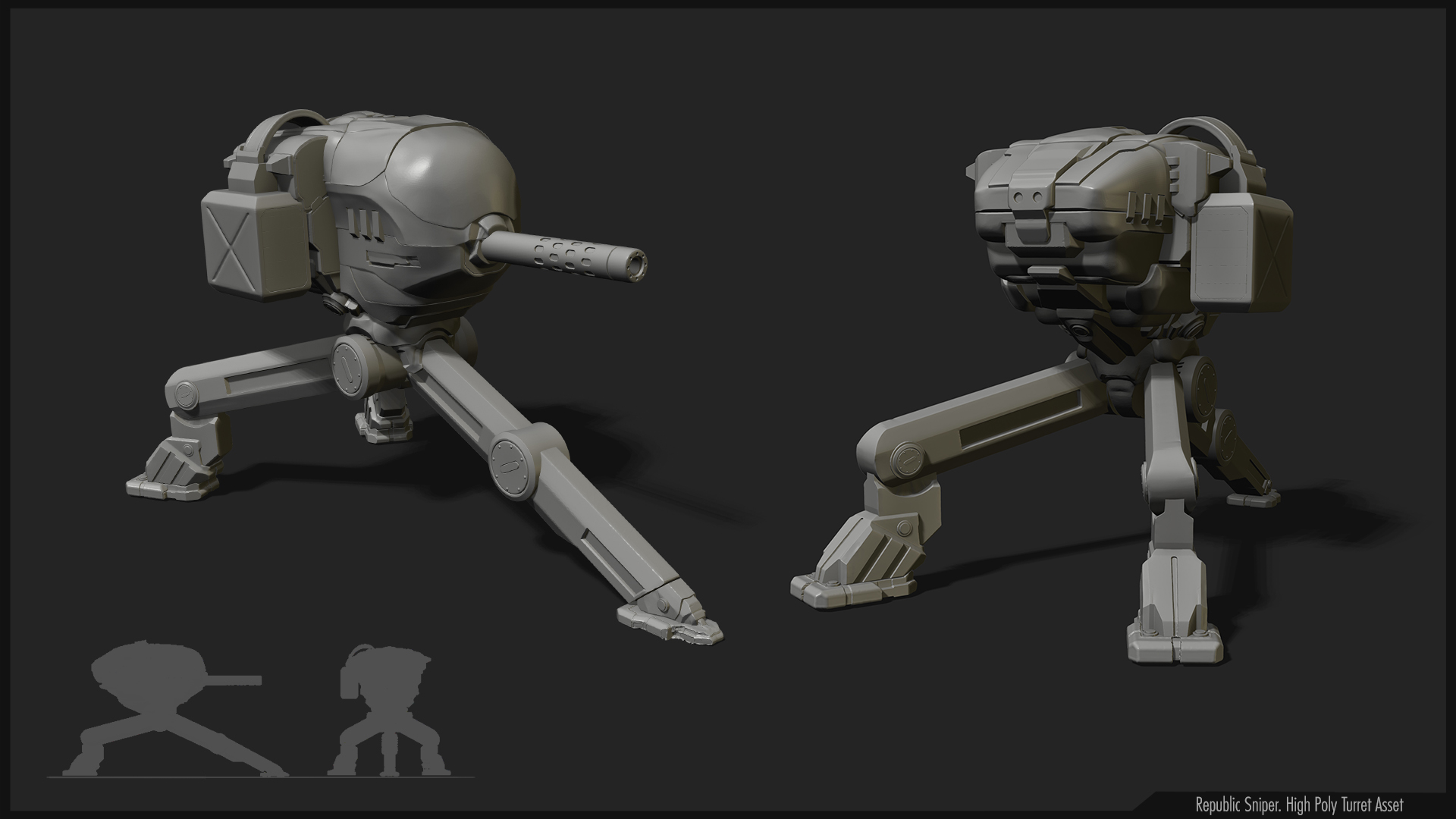

Automated turrets have taken the place of holographic soldiers on the training range and on some levels. This one is a Seditionist variant.

Last Friday, the team shipped a fully operational tech demo using the new movement mechanic. We’ll be testing this internally for a few weeks, then we’ll start integrating the amazing work Patrick and Alex, our 3D Artists, have been doing with environments, props, and characters, as well as the UI concept work being done by the MartianCraft Design team.

The Republic and Seditionist turrets are built from many of the same parts, but the Republic version (seen here) is more polished and high-tech.

It’s an exciting time to be making games. Republic Sniper has taken far longer than anticipated, but I’m feeling really good about how it’s coming together. I can’t wait to share it with you, sign-up here to find out when it’s available or you can follow progress on Twitter.